All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in November 2023.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in November 2023.

- Ancient Rome

- Ancient RomeIn this page:

Almost a Movie Set in the American Far West

Clash with the Greek World

The First Punic War

The Second Punic War

Crisis, Despair and Resurrection

Iconography

The Romans by defeating the Volsci had the opportunity to increase their contacts

with the rich Greek colonies of Campania Felix (happy countryside), the fertile coastal plain located north of the Gulf of Naples. They also got in touch with

another Italic people, the Samnites, who controlled the southern Apennines, including some key

passes. At the beginning relations with the Samnites were peaceful: a treaty was signed in 354 to

establish trading rights and define the respective areas of influence.

In 343, just a few years later, the treaty was broken, as the Romans sided with the towns on the coast which were threatened by the Samnites.

The first war against them had an unexpected end: the Romans defeated the Samnites twice, but soon after made an alliance

with them to gain their assistance in submitting to the direct rule of Rome several

towns of southern Latium, which had retained some independence. It was during this second part

of the war that an isolated column was erected for the first time in the Forum: it celebrated Gaius Menius,

a consul who had seized Antium (Anzio).

(left) Honorary columns in Foro Romano;

(right) Temple B (round) in Largo di Torre Argentina

The conflict between the Romans and the Samnites started again in 326; the Greek aristocracy of

Neapolis (today's Naples), scared by the continuous increase of Samnite immigrants, turned to Rome for help.

In 321

the Roman consuls

decided to directly attack the Samnite territory; they moved with almost all the Roman army through the narrow valley of the river

Caudio to lay siege to the Samnite town of Maleventum (bad event). The legions did not meet resistance, but at the last gorge before the town, they found that the road was

obstructed

by trees and rocks, so that they could not proceed; the consuls decided to go back to the

coastal plain, but in the meantime the Samnites had blocked also the initial gorge giving access to the valley.

At that point the dismayed Romans saw the Samnite warriors on the ridges of the mountains and understood that they

were trapped. At night the Samnites lit fires and moved them around scaring the Romans even more.

The Romans had little knowledge of the territory and their attempts to find a way out through the mountains were easily

repelled by the Samnites; the consuls sent messengers to the enemy saying that they had the authority to reach

a peace agreement on behalf of Rome; the Samnites accepted, but imposed very heavy conditions:

the Romans had to leave all their weapons and other military equipment and had to pass under

a yoke formed with three spears, the Caudine Forks, before being allowed to return to Rome. "To go through the Caudine Forks" is a

sentence still used to mean a

difficult passage in life.

It took five years for the Romans to digest that humiliation: in 315 they broke the treaty and for ten years the

two sides fought with renewed vigour. A peace treaty in 304 did not close the conflict which started again in 298. The Samnites

incited rebellions in the towns north of Rome, but over time the Romans managed to surround

the Samnite territory with newly founded colonies. The 290 peace

treaty which put an end to the third war, established the supremacy of Rome in the Italian peninsula; the Samnites retained their

territories in the mountains, but their "foreign" policy had to be approved by Rome.

The Samnite wars led the Romans to gain a better knowledge of the Greek world and this was

reflected in more complex buildings, as shown by the round temple in Largo di Torre Argentina.

The growing influence of Rome in southern Italy was seen as a potential threat by Tarentum (today's Taranto), a Greek colony founded by the Spartans. Its natural harbour was well protected from both heavy seas and enemy attacks and Tarentum was a very rich town.

Staatliche Antikensammlungen of Munich: kylix, a wine-drinking cup, by the Underworld Painter of Tarentum (late IVth century BC) depicting Hades and Persephone, a subject which was popular in the Greek cities in Italy, e.g. at Selinunte and Locri

In 282 the Romans violated the terms of the peace treaty they had signed in 302 with Tarentum. The Greeks turned for help to Pyrrhus, king of Epirus, a mountainous region on the Ionian coast of today's Greece. Pyrrhus landed in Italy with an army of 20,000 troops, a cavalry of 3,000 and 26 elephants. The first battle with the Romans took place at Heraclea, a few miles to the west of Tarentum. The Greek line of battle arranged in phalanxes and the elephants, animals the Romans were not familiar with, were the two key factors which led Pyrrhus to victory. He moved towards Rome and won a second battle, but the losses he suffered were such that he offered a peace treaty to the Romans (hence Pyrrhus' victory to mean a victory which has a significant cost). The Senate refused and Pyrrhus preferred not to attempt to seize Rome.

Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia: IIIrd century BC votive plate depicting a war elephant from Capena

The Greek colonies in Sicily asked Pyrrhus to help them in repelling the Carthaginians, who from Lilibaeum, a town they had founded at the western

tip of Sicily, were trying to conquer the whole island. Rome and Carthage made an alliance against Pyrrhus; the Carthaginians

lost most of their possessions in Sicily, but held onto Lilibaeum: the war went on until some Greek towns, wary of the

financial cost of financially supporting Pyrrhus, made peace with Carthage.

Pyrrhus returned to the continent and moved towards Rome, but at Maleventum he was defeated

by the Romans and with the rest of his army he fled back to Epirus. The Romans changed the name of

the town to Beneventum (good event) today's Benevento.

(left to right) Clean shaven emperor (Trajan - Musei Vaticani); emperor with a light beard (Hadrian,

found at Sagalassos, now at the Museum of Burdur in Turkey); emperor

with a complex beard (Septimius Severus - Museo Nazionale Romano)

Tarentum and the other Greek colonies which had supported Pyrrhus were forced to reach peace

agreements with Rome and to acknowledge it as the leading power on the Italian peninsula. In order to retain

part of their territories and trading privileges they had to pay; they gave the Romans not only gold and silver,

but also slaves.

We generally associate slavery with very painful jobs in mines and plantations,

but some of the slaves who came from the Greek colonies had skills which

were appreciated by the Roman upper classes.

Apparently there were not good barbers in Rome, prior to the

arrival of slaves who were very experienced barbers. The early Romans did not pay too much

attention to their appearance and did not shave on a daily basis: the availability of good

barbers brought a change and for the following centuries all the

portraits of consuls, politicians and emperors showed well shaved faces.

This lasted until Emperor Trajan, with the remarkable exception of Nero; Hadrian, Trajan's successor, preferred to be portrayed with a light beard.

At the time of Emperor Septimius Severus the beard became even more prominent.

The long fight with Carthage is a key component of the myth of Rome: by defeating the

city founded by the Phoenician Queen Dido not far from today's Tunis, Rome became the emerging

power of the Mediterranean: when Virgil, at the suggestion of Augustus, devised a poem meant

to give Rome a noble origin, he wrote some of his best verses on the "love and death" story between

the hero of his poem, the Trojan prince Aeneas, and the Carthaginian queen.

By celebrating the strength and wealth of Carthage, Virgil knew he was celebrating Rome;

Dido's brother Pygmalion, who had killed her husband Sicaeus, forced her to flee Tyre.

She escaped to a site in northern Africa where she founded Carthage; soon after

Aeneas was stranded by a sea storm on the shores near the new city: he was hosted and

well received by the queen and Venus, who protected Aeneas,

asked her son Cupid to throw one of his arrows to make the queen fall in love with the Trojan prince: they passionately

loved each other until Aeneas was reminded by Hermes that his destiny was to leave for Italy where

his descendants would found Rome.

When the sails of Aeneas' ship disappeared over the horizon, Dido killed

herself swearing eternal hatred of Rome. You may wish to see a Roman floor mosaic from Dorchester which illustrates Virgil's account.

As a matter of fact the initial relations between

Rome and Carthage were friendly for almost 250 years as the first commercial treaty between them

was signed in 510. The two powers had made a military alliance against Pyrrhus and by forcing him out of Sicily

and the Italian peninsula they realized that the remaining independent Greek

colonies had become easily conquerable.

Carthage wanted to expand its influence on the eastern part of Sicily and in particular on

Syracuse; the Romans had already a foot on the island, as Messina was in the hands of mercenaries from Campania;

the casus belli (the situation or act justifying the war) was a quarrel between

Messina and Syracuse; the surprising thing in this first Punic (Phoenician) war is

that the Romans lost on land and won at sea. In 241 the Roman fleet defeated that of the Carthaginians near the north-western tip of Sicily.

Carthage gave up its Sicilian colonies and in 238 also those it had in Sardinia;

the two islands (with the addition in 227 of Corsica) became the first Roman "provinces", direct possessions of the Roman Senate.

Museo Nazionale Romano at Cripta di Balbo: (left) fragment of Forma Urbis Severiana, a marble plan of Rome at the time of Emperor Septimius Severus, showing the site of a theatre (it was affixed at Tempio della Pace); (centre) funerary altar of L. Aufidius Aprilis who had a shop near Teatro di Balbo; (right) reconstructed arch of the theatre. Until a few years ago the ruins were thought

to belong to Circus Flaminius

During the period of the Punic Wars the decision-making role of the patricians was challenged by the ever growing

number of plebeians, the commoners of Ancient Rome.

They used to congregate outside the walls in the then almost empty space of

Campus Martius; the importance of these meetings was eventually acknowledged

by the Senate through the building of a circus where the plebeians could meet and discuss in a more

structured way (the patricians made use of Circus Maximus).

The circus was named Flaminius after the Consul Gaius Flaminius Nepos who was in charge when in 221 the circus was built.

The ruins of the circus were for centuries thought to be inside the houses along Via delle Botteghe

Oscure (south side), but it is now thought that the circus was completely

pulled down by Augustus and that a few years later Lucius Cornelius Balbus built on that same site a theatre, the ruins

of which are those inside the houses of Via delle Botteghe Oscure. Most of these houses

were acquired by the Italian State in 1981 and they now house a section of

Museo Nazionale Romano (the other three sections being located at Terme di Diocleziano, Palazzo Massimo alle Terme and Palazzo Altemps).

The Carthaginians reacted to the loss of Sicily and Sardinia by expanding their influence in Spain where they

already had a colony (Gades, today's Cadiz). They conquered almost all of the southern half

of the country, which had important mining districts. Rome became wary of the rapid recovery of Carthage and in 226 imposed

a limit to the expansion of the Carthaginians in Spain. The treaty however left Saguntum,

a coastal town, with which Rome had made an alliance, in the Carthaginian sphere of influence.

In 219 while the Roman Senate was still

pondering on how to deal with this issue, the Carthaginians laid siege to Saguntum and seized it (Dum Romae consulitur, Saguntum expugnatur).

Eventually Rome asked the Carthaginians to leave Saguntum; at their refusal it declared war.

The Carthaginians in Spain were led by Hannibal Barca then aged 29; he did not lose time

and moved towards southern France; in the summer of 218 he crossed

the Alps, most likely through the Little Saint Bernard Pass, a very difficult task considering

that he had brought with his army a certain number of elephants (maybe 37). The Romans had split

their forces by sending an expedition to Spain and another army to Sicily to protect their recent acquisitions.

The legions in charge of the defence of Rome met with the Carthaginians

in northern Italy and were defeated by Hannibal. The legions in Sicily were recalled and

rapidly reached northern Italy to stop Hannibal but they were defeated too. The Gauls living

in the Po Valley, who had been subdued by the Romans just a few years before, joined their forces

with the Carthaginians. In 217 Hannibal crossed the Apennines and moved towards Rome: near Lake Trasimeno the Romans suffered a third defeat (see a XVIth century fresco depicting the battle).

(edited) Section of a modern marble map on the rear wall of Basilica di Massenzio

Hannibal did not have a supply chain to support his army and thus he relied on the help of the towns which rebelled against Rome or on the sacking of those which resisted him. He therefore was hit by the new Roman tactics, devised by the dictator Fabius Maximus, who by a sort of guerrilla actions set fire to the territories of the towns which in one way or another would have fallen into Carthaginians hands; he also avoided a direct confrontation with the enemy: he thus gained time to reorganize the Roman army; for this reason he was called Cunctator (the Temporizer).

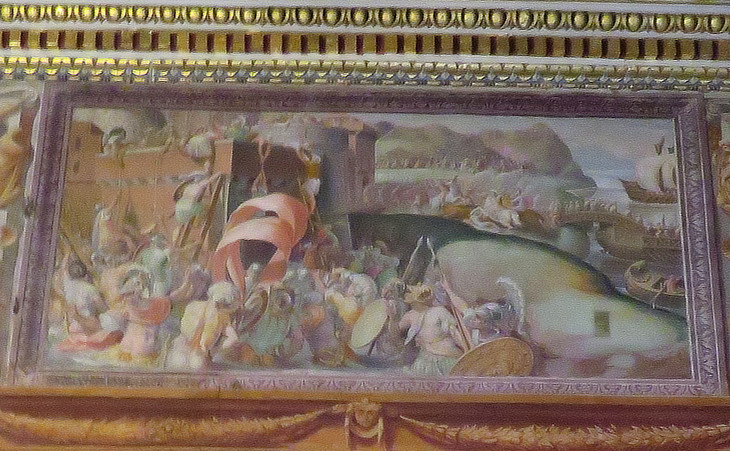

Fresco at Galleria delle Mappe Geografiche in the corridors of Palazzo del Belvedere in Rome

showing (left) the Roman and the Carthaginian camps and (right) the Battle of Cannae

The consuls who replaced Fabius Maximus at the end of his six months in office thought they had enough forces to engage Hannibal, who in the meantime had made an alliance with the Samnites and had reached southern Italy. At Cannae the Romans were again defeated: this battle was among the bloodiest ones of ancient history, with more than 50,000 Roman casualties.

At the news of the Cannae defeat the Romans were struck with terror: signs of the imminent fall of the city were identified in many extraordinary events: births of children with characteristics of both sexes, temples struck by lightning when there were no clouds in the sky, strange behaviour of animals. While some Romans worked at organizing a last defence, others believed that only a supernatural intervention could save Rome. It is during the Second Punic War that new deities (e.g. Cybele) became popular in Rome and temples were dedicated to them in the belief that they could help the Roman armies in defeating the Carthaginians. A precedent had been set in 293 when the cult of Aesculapius (the Greek god Asclepius) was introduced in Rome to put an end to a pestilence.

(left) Small cylindrical Christian monument inside S. Bartolomeo all'Isola,

thought to be a sacred well of the Temple to Aesculapius; (right) relief at the eastern tip of Isola Tiberina,

showing a man (whose face has been smashed) holding a serpent-entwined rod, the symbol of

the god

Eventually Hannibal did not move towards Rome; in the following years the Romans returned to a careful strategy of containment of the enemy: to prevent Carthage from sending reinforcements to Hannibal, they attacked the Carthaginian possessions in Spain. In 212 they seized Syracuse and gained control of all Sicily. In 211 they occupied Capua, which had become Hannibal's headquarters. According to Livy Carthaginiensium exercitum, quem neque nives neque Alpes debilitaverant, otia Campaniae enervaverunt (the Carthaginian army, which had not been weakened neither by the snow, nor by the Alps, lost its strength while resting in Campania), the so called Capua leisure. Over time the isolated army of Hannibal was no longer a real threat to the security of Rome: an attempt by his brother Hasdrubal to bring new forces and raise again the Gauls against Rome was repelled in 207 near Fano.

Palazzo dei Conservatori - Sala degli Arazzi: 1544 fresco depicting the Siege of Carthage by Scipio

In 204 the consul Publius Cornelius Scipio landed south of Carthage and moved towards Carthage; Hannibal returned to defend his own city, but in 202 at Zama, the Carthaginians were defeated. The subsequent peace treaty gave Rome full control of the Carthaginian territories in Spain and imposed strict limits on the size of the Carthaginian fleet and on its foreign policy. Scipio was given the title of Africanus for his victories in that land (the Romans called Africa what is today's Tunisia).

The following links show works of art portraying characters and events

mentioned in this page (they open in another window):

Aeneas and Venus by Tiepolo.

Dido's death by Guercino.

Hannibal crossing the Alps by J. M. W. Turner

Napoleon crossing the Alps by J. L. David (the name of Hannibal is written in the left lower corner).

Hannibal portrayed as Turk fresco by Jacopo Ripanda at Palazzo dei Conservatori.

Victor Mature as Hannibal.

Previous pages:

I - The Foundation and the Early Days of Rome

II - The Early Republican Period

Next page:

Expansion in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Image used as background for this page: detail of the elephant in Piazza della Minerva in Rome.