All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in August 2024.

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it.

Notes:

Page revised in August 2024.

- Modern Rome

- Modern RomeIn this page:

Pope Sixtus V

The Foundation of Modern Rome

Pope Clement VIII

Favourable Developments

Pope Paul V

An Artistic Centre

Famous Trials

Iconography

In the conclave which followed the death of Pope Gregory XIII in April 1585 the cardinals soon reached

an unanimous agreement on the election of Cardinal Felice Peretti, also known as Cardinal Montalto (after the small town in the Marches near Ripatransone where he

joined the Franciscan Order).

According to tradition, during the conclave he feigned being very ill and thus gained

the support of the cardinals who preferred a weak pope; historians agree that a key factor

in his election was the support he had from Cardinal Ferdinando de' Medici who lobbied for him.

During the pontificate of Pope Gregory XIII, Cardinal Peretti maintained a very low profile and seemed almost completely absorbed in embellishing his villa near S. Maria Maggiore. He was appointed cardinal by

Pope Pius V and he shared the religious zeal of that pope;

for this reason he disliked the more lenient attitude of Pope Gregory XIII; in addition, being a Franciscan, he regarded with suspicion the growing importance of the Jesuits, who were favoured by the Pope.

He chose to be called Sixtus V, a tribute to Pope Sixtus IV who was for years at the head

of the Franciscan order and who promoted Renovatio Urbis, a plan for the development of Rome as a Christian Holy City.

The new pope immediately tackled the lawlessness into which Rome and the Papal State had fallen

during the last years of Pope Gregory's pontificate. Non veni pacem mittere, sed gladium - I did not come to bring peace, but the sword (of justice) - he told a

cardinal who congratulated him on his election. Four youngsters who had attended the papal procession carrying weapons were arrested

and put to death. For some time the sight of bodies hanging from gallows or of beheaded

heads at the top of pikes became common in Rome; in 1587

a medal coined by the Pope announced that the papal "Law and Order" policy had achieved its objective: it portrayed a pilgrim peacefully resting at the foot of a tree and the inscription Perfecta securitas (it is shown in the image used as background for this page).

(left) S. Maria Maggiore: model of Capella Sistina by Sebastiano Torregiani; (right) Statue of Pope Sixtus V by il Valsoldo in the chapel

Pope Sixtus V had a predilection for S. Maria Maggiore; he greatly improved the access to the basilica by opening streets which departed from it and

reached S. Croce in Gerusalemme, S. Giovanni in Laterano, S. Lorenzo in Panisperna and SS. TrinitÓ dei Monti (learn more details on these streets and see them in the 1781 Map of Rome by Giuseppe Vasi).

Pope Sixtus V chose to be buried in S. Maria Maggiore in a new chapel which is almost a separate church and which was named after

him. He wanted to be portrayed in a

very humble position: not seated on the papal throne (as he was depicted in many bronze statues in the Marches, e.g. at Loreto), but praying on his knees, without

the crown. Eventually some other popes were shown on their knees, e.g. Bernini did that in the Monument to Alexander VII (left) and Antonio Canova in that to Clement XIII (right) (it opens in another window).

Pope Sixtus V tackled other issues with the same resolution he showed in restoring security.

He redesigned the structure of the papal government by creating fifteen Congregazioni, permanent committees of the College of

Cardinals having jurisdiction over a specific branch of the administration, a sort of modern government department. The congregazioni however were only asked to advise the pope on the best course of action as he retained the last word.

He dismissed the tradition of discussing the most important decisions in concistorio (in a meeting with the cardinals): these meetings became purely formal. He also increased the number of Italian cardinals with the aim of reducing the influence of Spain on the

election of the pope and in general on the policies followed by the popes.

He also improved the financial situation he had inherited from his predecessor by

increasing taxation which was mainly based on gabelle, duties collected on the goods entering a town. He called two extraordinary Jubilee Years in 1585 and 1590 which helped in collecting additional revenues.

He had a difficult relationship with Philip II, King of Spain: he supported the king's attempt to invade England, but he resisted Philip's calls for a more resolute papal

intervention against Henry of Navarre, who, following the 1589 murder (by a monk) of Henry III (the third son of Catherine de Medici)

was the legitimate heir to the French throne.

Henry was the head of the Huguenots, but the Pope was wary that Philip was trying to claim that throne for his own daughter Isabella.

He preferred to call a Jubilee Year to pray for the restoration of a Catholic king on the French throne, rather than financially support Philip.

Biblioteca Vaticana: Piazza di S. Giovanni in Laterano after it was redesigned by Pope Sixtus V

The landscape of Rome when Pope Sixtus V was elected was marked by a sort of

gigantic ruin: the unfinished S. Pietro Nuovo: four gigantic pillars stood out supporting an empty drum, very much resembling those of

Caracalla's Baths: the leading architects of the time had doubts whether these pillars could support the dome envisaged by Michelangelo: the Pope pushed for moving ahead:

in January 1587 he ordered Giacomo Della Porta to build the missing dome: with a workforce of

800 he was able in just two years to accomplish a task which many thought would require ten years at least. He tackled with his usual resolution the never ending issue about what to do with the many remaining monuments of Ancient Rome: he decided that either they could be

turned into a Christian monument or they had to be pulled down and their marbles used for the decoration of churches. What remained of the Septizodium was pulled down and its columns and

marbles were used for his chapel at S. Maria Maggiore. Colosseo risked being pulled down too to open a new street, but Cardinal Giulio Antonio Santorio and others succeeded in persuading the Pope to spare the very symbol of Ancient Rome.

The ancient obelisks were seen as the first arm of a cross and four of them were restored and

relocated in Piazza S. Pietro, Piazza di S. Giovanni in Laterano, Piazza del Popolo and in front of the apse of S. Maria Maggiore.

The Pope placed a cross at their top and new inscriptions on their pedestals explaining

how these monuments to the pagan gods were now celebrating the triumph of the True Faith. He turned Colonna Traiana and Colonna Antonina into monuments to St. Peter and St. Paul.

Rome in a late XVIth century fresco at Galleria delle Mappe Geografiche in the corridors of Palazzo del Belvedere in Rome; the size of the obelisks and of the columns is emphasized

The Pope's heraldic symbols (a lion holding pears, three mountains and a star) appear on very many monuments of Rome which he built or completed:

a) Porta Furba and another triumphal arch near Porta S. Lorenzo celebrate the completion of a new aqueduct which supplied water to 27 fountains among which Mostra dell'Acqua Felice, fontana di Piazza dei Monti and fontana di Piazza d'Aracoeli;

b) S. Girolamo degli Schiavoni, Loggia delle Benedizioni in S. Giovanni in Laterano, the steps of the fašade of SS. TrinitÓ dei Monti are all decorated with his lion while during his pontificate the fašade of S. Luigi dei Francesi was completed;

c) he entirely renovated Palazzo del Laterano (see a page on its ceilings) and built Scala Santa next to it; he continued the

construction of Archiginnasio della Sapienza, he relocated Biblioteca Vaticana in a new building of Palazzo Apostolico and he modified the entrance to Palazzo della Cancelleria. He placed some ancient statues on the balustrade of Piazza del Campidoglio.

See a section on a 1588 Guide which describes Rome at the time of Pope Sixtus V.

Pope Sixtus V died of malaria in August 1590: he was followed by three popes whose pontificates were very short: Pope Urban VII: 13 days; Pope Gregory XIV: 10 months; Pope Innocent IX: 2 months. Pia civitas in bello (Pious city involved in war), the Prophecy of Malachy associated

with Pope Innocent IX seems a reference to the military (and financial) intervention of the

Pope in the war in France: Gregory XIV abandoned the prudent policy of Pope Sixtus V and spent a fortune to support a military expedition: the "prophecy" suggested a continuation of that effort.

At the conclave which in January 1592 followed the death of Pope Innocent IX

the cardinals were determined to choose a man who could ensure the stability of the Papal State

and who would not entirely accept the policies suggested by the King of Spain.

The choice fell on Cardinal Ippolito Aldobrandini who belonged to a rich Florentine family.

He was very devout and often fasted or visited the Seven Churches. He chose to be called Pope Clement VIII.

During his pontificate the Counter-Reformation process was completed with the publication in 1592 of Vulgata Clementina the official (Latin) Roman Catholic

version of the Bible: this text was used until 1979 when it was replaced by Nova Vulgata, a new text commissioned by Pope Paul VI.

Theological disputes, which to some degree reflected the rivalry between the Jesuits and the other orders, continued throughout his pontificate and

the same applies to the fight against the heretics. On February 17, 1600 at Campo dei Fiori, Giordano Bruno, a Dominican monk, was burned at the stake for holding opinions contrary to the Catholic Faith. The sentence was issued after a trial which lasted seven years.

(left) Detail of a fresco in the transept of S. Giovanni in Laterano having the appearance of a tapestry; (right) S. Maria sopra Minerva - Cappella Aldobrandini: ceiling by Cherubino Alberti

Pope Clement VIII was a pious man, but this does not mean that he did not indulge

in a practice formally condemned by all the popes but too tempting to resist: he appointed three of his nephews cardinals and other members of the family were given important positions.

The stars and the stripes

of the Aldobrandini coat of arms soon appeared on the walls of churches, palaces and villas built by the Pope or other members of his family.

Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini in particular built a very large villa in Frascati and bought another one on the Quirinale hill.

During the pontificate of Pope Clement VIII some features of what was later on called Baroque style,

started to gradually appear in the Mannerist decoration of the transept of S. Giovanni in Laterano: the frescoes were framed by a painted tapestry rather than by a traditional cornice;

in the Aldobrandini chapel in S. Maria sopra Minerva the ceiling was painted as if it were open and it showed the sky: these are both examples of illusionism (the use of perspective and other methods to give an appearance of three-dimensionality),

a technique which was greatly developed during the XVIIth century, especially in the decoration of ceilings.

Paris vaut bien une messe (Paris is worth a mass) according to tradition is the

rather cynical statement by which Henry of Navarre justified in July 1593

his decision to convert to Catholicism. This decision paved the way towards his acceptance by the Parisians as the legitimate king.

He was anointed Henry IV in February 1594 and in the next year Pope Clement VIII revoked the ecclesiastical sanctions against him. In 1598 the Pope favoured the Peace of Vervins

between Philip II of Spain and Henry IV thus bringing the French war of religions to an end.

Pope Clement VIII supported the Habsburgs in containing an attempt by the Ottomans

to conquer some border regions: he sent money and troops in 1595, 1598 and 1601;

his nephew Gian Francesco Aldobrandini and Lello Frangipane

died in these campaigns.

In the early XVIth century Pope Julius II vainly tried in

two wars to acquire Ferrara; in 1598 Pope Clement VIII managed to reach

this long standing objective of the papal policy peacefully, helped by the fact that at the death of the ruling duke (Alfonso d'Este), Henry IV of

France did not support the claims of his nephew (Cesare d'Este), thus betraying an alliance with the Este which had lasted for nearly a century.

In 1598 Rome was hit by the most severe recorded flood which caused

immense damage and ruined a bridge rebuilt a few years earlier.

Notwithstanding this dramatic event Rome was at its best to meet the many pilgrims who came for the 1600 Jubilee Year.

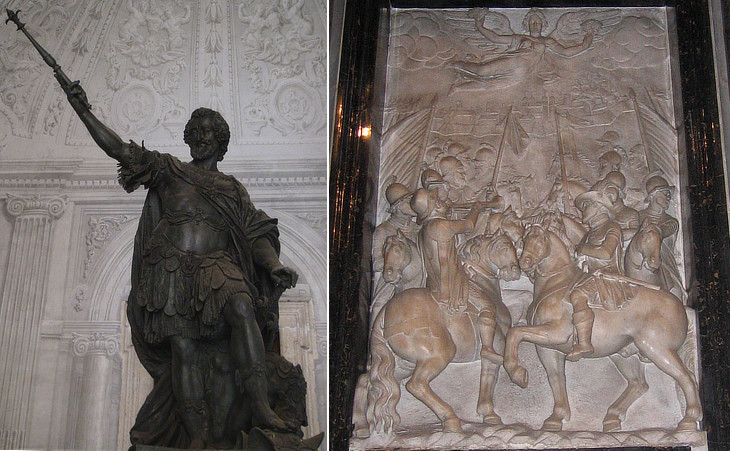

(left) Side portico of S. Giovanni in Laterano: monument to King Henry IV of France by Nicolas Cordier;

(right) S. Maria Maggiore - Cappella Paolina: relief celebrating the annexation of Ferrara

Relations between Pope Clement VIII and Henry IV of France became so good that the Pope agreed to annul Henry's marriage with Marguerite of Valois after 27 years. The King soon married Maria de' Medici, niece of Ferdinand I, Grand Duke of Tuscany. The former Huguenot who narrowly escaped being murdered at St. Bartholomew's Day, became a champion of the Church to the point that in 1606 (shortly after the death of the

Pope) a bronze statue portraying him as a Roman emperor was placed in S. Giovanni in Laterano; the Pope erected a small monument celebrating the Peace of Vervins

outside S. Maria Maggiore and made reference to the king in many inscriptions, including the gigantic one which he placed on the fašade of Palazzo Senatorio.

Pope Clement VIII did not start any major new buildings,

but was busy completing those initiated by Pope Sixtus V. He went ahead with the decoration of

S. Pietro where he built Cappella Clementina and he completed Palazzo Apostolico; in S. Giovanni in Laterano he renovated the transept and built a gigantic altar and a similarly gigantic organ.

Directly or through his nephews the Pope promoted the restoration of several churches: S. Nicol˛ in Carcere, S. Cesareo, S. Prassede; other cardinals took care of

S. Maria della Vallicella, S. Susanna and SS. Nereo and Achilleo (in

this church Cardinal Cesare Baronio applied the iconographical plan which emphasized the role of the Roman Church in the early centuries of Christianity by portraying the martyrdoms of the first saints).

The Pope built also Collegio Clementino and Palazzo del Monte di PietÓ. In 1600 the incorrupt body of St. Cecilia was re-discovered and it was portrayed in a famous statue by Stefano Maderno.

The conclave which followed the death of Pope Clement VIII showed the growing importance of France: King Henry IV with the help of the Aldobrandini cardinals was successful in

supporting the election of Cardinal Alessandro de' Medici, who had been nuncio in Paris and was a (distant)

relative of his second wife. He became Pope Leo XI, but his pontificate was very short: only 26 days. Sic florui the inscription on his funerary monument is a reference indicating that he was in blossom for just a few days.

At the following conclave the cardinals, after eight days of heated debate,

elected Cardinal Camillo Borghese who at the time was leading the Inquisition and was not

regarded as belonging either to the Spanish or to the French party.

His rigid views on the superior authority of the pope soon led him into a confrontation with the

Republic of Venice which clearly showed that the times when an excommunication was

able to force an emperor to kiss the pope's slipper to ask forgiveness had gone.

The issue at stake was related to the jurisdiction over

two priests (actually two noblemen having some ecclesiastical benefits) arrested and charged

with several crimes. The Pope claimed through his nuncio that they should be tried in Rome.

The Venetian Senate refused and the Pope excommunicated

the entire government of Venice and placed an interdict on the city.

To his great dismay the clergy (with the exception of the Jesuits and two other orders)

sided with the Republic; masses, weddings, funerals

continued to be celebrated. Eventually in March 1607 Pope Paul V withdrew his censure without

being able to force Venice to make concessions: the Jesuits remained banned from Venice for nearly sixty years.

S. Maria Maggiore - Cappella Paolina: (left) detail of a relief portraying Cardinal Scipione Caffarelli Borghese

and Pope Paul V; (right) heraldic symbols of the Borghese family

One of the first decisions of Pope Paul V was that of appointing cardinal his nephew Scipione Caffarelli, who added to his surname that of the Borghese

and adopted his uncle's coat of arms.

The eagles and dragons of the Borghese soon appeared on the many buildings erected or modified by the Pope and his nephew.

A relief in Cappella Paolina, a chapel in S. Maria Maggiore

where the Pope placed the funerary monument of Pope Clement VIII and his own, shows the Pope with his nephew: the chapel

was decorated with many references to the family's heraldic symbols. The Pope erected in front of the church a high column

and placed on its top a statue of the Virgin Mary; this led to the erection of many similar monuments, e.g. at Vienna and Munich.

Basilica di S. Sebastiano was in such poor condition that Pope Sixtus V replaced it in the traditional pilgrimage to the seven basilicas with S. Maria del Popolo.

Cardinal Scipione Borghese entirely renovated the old building which was again "promoted" to its pristine importance. He also renovated (at a later time) S. Grisogono and S. Gregorio Magno.

Pope Paul V overcame the reluctance of some cardinals to pulling down the fašade of old S. Pietro and went ahead with a project

which changed the shape of the new basilica and resulted in a new fašade (see the inscription celebrating the Pope).

Another gigantic inscription celebrated the Pope's restoration of a Roman aqueduct (renamed by him Acqua Paola)

which supplied water to Trastevere and Borgo where many fountains were built, e.g. those near Collegio Ecclesiastico,

in Piazza S. Pietro and in the Vatican Gardens.

In 1555 Emperor Charles V reached an agreement (Peace of Augsburg) with the German Lutheran leaders, based

on the principle that the prevailing religion in each of the more than 200 states into which Germany was divided would be that chosen by their respective rulers

(in some cases a bishop). This principle (cuius religio, eius religio) eventually led to a split among the Protestants

when the rulers of some important states (Palatinate, Nassau, Hesse and Brandeburg) converted to Calvinism, a faith not considered by the 1555 agreements.

In 1608 the Calvinists formed an alliance to protect their rights;

the Catholic sovereigns joined a similar league. Matthias, the last of a series of Habsburg emperors who had a tolerant religious policy, in 1617 indicated that his successor would be his cousin Ferdinand

who was known as a fervent Catholic (he was

brought up by the Jesuits). For this reason in May 1618 the Calvinists of Prague refused to recognize Ferdinand's

representatives and threw them out of the

windows of the royal palace in Prague.

This event started the Thirty Years' War a period of religious and national wars which lasted until 1648.

Pope Paul V financially supported Ferdinand who in 1619 at the death of Matthias became Emperor Ferdinand II. The Calvinists and the Lutherans revolted against the Habsburgs and Ferdinand sought the help of Spain: at the

Battle of the White Mountain the Protestants were defeated and the imperial authority over Bohemia was restored; this meant the return of that country to Catholicism. The event was celebrated in Rome by dedicating to it S. Maria della Vittoria.

Another important event which occurred during the pontificate of Pope Paul V was the 1616 condemnation of the Copernican doctrine by the Inquisition. The heliocentric theories supported

by Copernicus had been known for some seventy years without being considered a heretical proposition; they were regarded with interest by Pope Clement VII and an

initial document explaining them was dedicated to Pope Paul III.

The views of some theologians that the words of the Bible and in particular

those of Joshua praying to God to stop the sun ought not to be taken literally were overridden by the members of the Inquisition panel of cardinals, who were worried that this approach could diminish the authority of the Bible.

(left) Wooden ceiling of S. Maria in Trastevere central panel by il Domenichino;

(right) Main altar of S. Maria in Vallicella with a movable section by Peter Paul Rubens

Pope Paul V and his nephew Cardinal Scipione Borghese were great collectors of works of

art: the family's city palace and suburban

villa housed a large collection which was not limited to

ancient statues

but included works of art of contemporary painters. The means the Borghese used to enrich their g/a>alleries were sometimes unscrupulous;

Pope Paul V confiscated 107 paintings collected by il Cavalier d'Arpino, then regarded as a very great painter, which

included the earliest works by Caravaggio; he gave them to his nephew and they are now among the masterpieces of Galleria Borghese. Pope Paul V set the usual residence of the popes in Palazzo del Quirinale which he enlarged and embellished with frescoes portraying the ambassadors he received from Persia and Japan.

The many palaces and churches built in the second half of the XVIth century needed to be decorated and this attracted

to Rome many painters from all over Italy, in particular from Bologna: the Carracci brothers, Guido Reni, Guercino and Domenichino left in Rome some of their finest works. Other painters came from Europe, in particular from the Flanders and France.

Temporary exhibition at Scuderie del Quirinale on Baroque Art in Genoa (March 2022): (left) Giovan Carlo Doria by Peter Paul Rubens (1606) - Galleria Nazionale di Palazzo Spinola - Genoa; (right) Agostino Pallavicini as ambassador to the Pope by Anthony Van Dyck (1621) - The J. Paul Getty Museum - Los Angeles. Both the Doria and the Pallavicini became members of the Roman nobility through marriages with the Pamphilj (in 1671) and the Rospigliosi (in 1670)

As the century advanced beyond the first decade three trends became prominent,

the impact of which was to be felt sooner or later throughout Italy and across her frontiers, namely the classicism of Annibale Carracci's school, Caravaggism, and Rubens's northern Baroque, the last resulting mainly from the wedding of Flemish realism and

Venetian colourism. This marriage, accomplished by a great genius, was extraordinarily

fertile and had a lasting influence above all in northern Italy. (..) In the course of the third decade Genoese painters all attempted to

cast away the last vestiges of Mannerism and turn towards a freer, naturalistic manner,

largely under the influence of Rubens and Van Dyck, a master of the official international style of portraiture.

Rudolf Wittkower - Art and Architecture in Italy 1600-1750

Towards the end of the pontificate of Pope Paul V (who died in 1621) Cardinal Maffeo Barberini introduced a young sculptor to Cardinal Scipione Borghese: young Gian Lorenzo Bernini was given by the latter his first important commission: a statue portraying Aeneas with his father and his son.

It was the beginning of a career which left a great mark on the artistic developments of the whole century.

The trial of Giordano Bruno was not the only great trial of the period covered in this page.

During the pontificate of Pope Gregory XIII in the general disregard of the law Cardinal Montalto was forced to tolerate the assassination of his nephew Francesco Mignucci,

by Paolo Giordano Orsini who was in love with Vittoria Accoramboni, Francesco's wife.

Once elected pope, Cardinal Montalto wanted to show he meant what he now preached about the force of the law.

Adultery was officially

regarded as a serious offence and was punished by death. In 1585 Roberto Altemps,

son of Cardinal Marco Sittico Altemps,

was charged with raping a young girl: this crime was usually settled with marriage,

but Roberto was already married; he was therefore tried and sentenced to death:

his father vainly called for mercy: the Pope was unmoved and Roberto was beheaded.

In 1599 Francesco Cenci the head of a rich family (with several palaces and fiefdoms)

disappeared from a castle he owned at Petrella del Salto in Abruzzo; he had an extremely bad reputation and had been charged with several crimes;

rumours spread about an involvement of his relatives in his disappearance; the papal police investigated and soon discovered that four members of the family were involved in Francesco's assassination

(Lucrezia, Francesco's second wife;

Giacomo and Beatrice son and daughter of Francesco's first marriage; Bernardo, a young boy, son of Francesco and Lucrezia).

Because of Francesco's reputation the people of Rome expected Pope Clement VIII to apply some mercy taking into account some mitigating circumstances. These expectations were not satisfied with the sole exception of Bernardo who had however to watch the execution of his relatives at Piazza di Ponte before returning to prison. The properties of the Cenci were confiscated. It is said that Caravaggio was in the crowd who watched the executions and

that some of his later paintings were influenced by what he saw.

(left) Monument to Roberto, Duke of Gallese, Cardinal Altemps' son next to Cappella di S. Maria della Clemenza in S. Maria in Trastevere; (right) assumed portrait of Beatrice Cenci by Guido Reni in

Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica di Palazzo Barberini

Cardinal Altemps dedicated a chapel to S. Maria della Clemenza

in what was a sort of mute criticism of the inflexibility shown by Pope Sixtus V. He buried his son outside the chapel:

a lengthy inscription lists the positions held by Roberto in his short life: Immature extinctu (immaturely dead)

is the only reference to the circumstances of his death: the inscription is signed by Roberto's wife, but the decision to

portray him almost as a boy was most likely made by the Cardinal.

In another wing is poor Beatrice Cenci, by Guido; - taken the night before her execution. It is a charming countenance; - full of sweetness, innocence, and resignation. Her step-mother hangs near her, by whose counsel, and that of her confessor, she was instigated to prevent an incest, by the "sacrifice" of her father; - but that, which she thought a sacrifice, was converted by her enemies into a "murder" - and she lost her head, by the hand of the executioner.

Henry Matthews - Diary of an Invalid - 1817/1818

Our visit to the Barberini Palace to-day was solely to view the famous portrait of Beatrice Cenci. Her appalling story is still as fresh in remembrance here, and her name and fate as familiar in the mouths of every class, as if instead of two centuries, she had lived two days ago. In spite of the innumerable copies and prints I have seen, I was more struck than I can express by the dying beauty of the Cenci. In the face the expression of heart-sinking anguish and terror is just not too strong, leaving the loveliness of the countenance unimpaired; and there is a woe-begone negligence in the streaming hair and loose drapery which adds to its deep pathos. It is consistent too with the circumstances under which the picture is traditionally said to have been painted that is, in the interval, between her torture and her execution.

Anna Jameson - Diary of an EnnuyÚe - 1826

Palazzo Giustiniani at Bassano - Camerino di Diana: The Sacrifice of Iphigenia by il Domenichino, a friend of Guido Reni (1609); the scene is based on Euripides' play, but it brings to mind the execution of Beatrice Cenci because the executioner is not a priest and he holds an axe rather than a knife and Iphigenia does not wear Greek clothes

The assumed portrait of Beatrice Cenci in prison by Guido Reni (together with the legend that on the anniversary of her death Beatrice left her grave in S. Pietro in Montorio to carry her severed head to Piazza di Ponte) inspired many writers including Stendhal, Shelley, Alfred Nobel, Dumas and Hawthorne.

The following links show works of art portraying characters and events

mentioned in this page; they open in another window:

Piazza S. Pietro in 1585 XVIth century engraving.

The relocation of the obelisk in Piazza S. Pietro XVIth century engraving.

Triumphal entry of Henry IV in Paris by Peter Paul Rubens (1577 - 1640) - Uffizi Gallery - Florence.

The arrival of Maria de' Medici in France by Peter Paul Rubens - Louvre - Paris.

Cardinal Scipione Borghese by Giuliano Finelli (1633) - Metropolitan Museum - New York.

The Defenestration of Prague XVIIth century engraving.

Judith by il Caravaggio (1573 - 1610) - Galleria Barberini - Rome.

The Sacrifice of Isaac by il Caravaggio - Uffizi Gallery - Florence.

Next page: Part III: Modern Rome

VI - The Age of Bernini

Previous pages: Part I: Ancient Rome:

I - The Foundation and the Early Days of Rome

II - The Early Republican Period

III - The Romans Meet the Elephants

IV - Expansion in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea

V - Pompey and Caesar

VI - Augustus

VII - From Tiberius to Nero

VIII - The Flavian Dynasty

IX - From Nerva to Marcus Aurelius

X - A Century of Turmoil (180-285)

XI - From Diocletian to Constantine

XII - The End of Ancient Rome

Part II: Medieval Rome:

I - Byzantine Rome

II - The Iron Age of Rome

III - The Investiture Controversy

IV - The Rise and Fall of Theocratic Power

V - The Popes Leave Rome

VI - From Chaos to Recovery

Part III: Modern Rome:

I - Rome's Early Renaissance

II - Splendour and Crisis

III - A Period of Change

IV - The Counter-Reformation